Brooklyn-based artist Lorna Simpson produces visual works that both isolate and confront conventional views on identity, ethnicity, and history. A majority of her recent work portrays black American women casually posed in standalone scenes or everyday interactions, inviting viewers—herself included—to question what divisions exist between society's past and present.

Lorna Simpson: Gathered, a recent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum that ended in late August, explored the unknown histories of vintage photographs of black Americans from the 1940s on through the 1950s. In the first part of the Gathered exhibition, Simpson collected fifty unmarked black & white photo-booth shots and combined them with her own abstract ink drawings displayed in cluster on a wall. The collection is called Please remind me of who I am, and though individual identities are unknown, a shared one seems to surface from how the work was displayed at the museum (seen below):

In the second part, Simpson acted as both artist and subject, replicating the poses of an unknown black woman in photographs taken in the late 1950s in Los Angeles. Simpson’s inspiration for the project came very much by accident after spending several months looking at several vintage photographs of this woman, many the artist had posted in her.

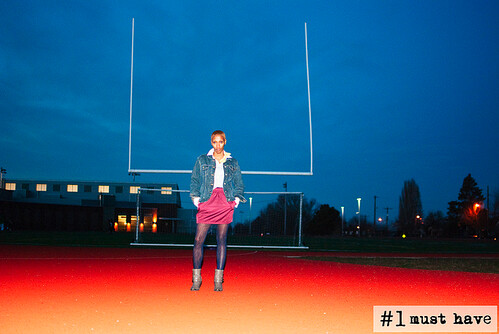

What appeals to me about this particular work is that Simpson unknowingly became part of the project over the course of nine months or so before having her Eureka! moment—Simpson was her own subject first, an artist second. Here's a split-image sample from Lorna Simpson: Gathered (that's the artist on the right in 2009).

Of the process, Simpson says:

It took time to figure out, well, what would you do with that as a piece other than it being someone’s archive of a project of performing for the camera? That is a very interesting process to me, not all [my] pieces come about that way […], but certainly when it does work like that it does mean taking a moment to step back and be conscious of the things around you, but also in that engagement there isn’t a timeline of completion. There isn’t a timeline of resolving how things get done, they kind of work themselves out.

Simpson shares more of how Gathered came to be, starting with her buying one or two vintage photos off eBay and then being asked by the seller if she wanted to buy the entire album. She did, at least of the 1957 images, connecting past to present and creating a shared identity between the unknown subject and herself (something she's never done before in her twenty-five plus years as an artist).

Simpson has used other visual media too, such as film and pencil, ink, and watercolor drawings through her tenure. Starting in the mid '90s, she's explored behavioral and relational topics using enlarged photographs placed on felt. One felt series features the photographed locations of separate undisclosed sexual encounters, accompanied by short narratives or dialogues. The people involved are missing, placing emphasis on what was said and seen, but not with who. Check out Simpson's The Rockand The Staircase.

Wigs and Wigs II, examines the social constructs, stereotypes, and assumptions that surround black hair textures and styles. The entire Wigs portfolio comprises over 50 hair portraits against pieces of cream-colored felt. Simpson spent over ten years exploring these two hair-focused works. Wigs II is seen here without its accompanying text panels:

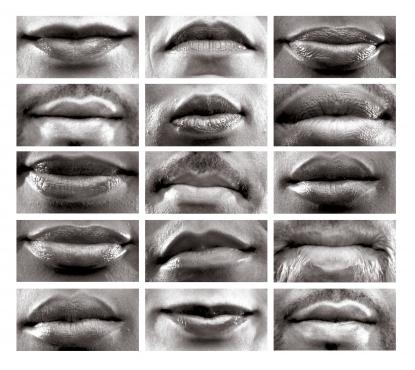

Simpson’s also worked with video and film and has a selection of her video works on her studio website. Easy to Remember (my favorite), features 15 mouths humming in unison to Rodgers and Hart’s 1935 “It’s Easy to Remember (And So Hard to Forget)” first performed by Bing Crosby in the movie Mississippi. Check out Simpon's Easy to Rememberhere.This particular video work was part of a larger exhibition in the early 2000s that included fifteen large photographic stills of the mouths accompanied with one-line narratives, such as "meaty,""sheer power," and "a voice that darkened with age." My favorite still includes the line, "her vocal chords were overtaken by the sound of her heartbeat." The 15 Mouths photo series is now part of the permanent collection at Studio Museum Harlem (seen below):

Simpson has had a lasting art career and rightly so—through art, she addresses topics that people take for granted, are afraid to broach, or accept as is. Needless to say, her work has been and hopefully will continue to be a catalyst for conversation on perceptions of identity and ethnicity, among others. Last year the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis featured Recollection: Lorna Simpson displaying six selected works spanning Simpson’s 25-year art career. She's covered a lot of visual ground—perhaps the Internet will be her next medium?

Previously: Angela Singer, Ana Benaroya

Positive representations of PWDs (People with disabilities) are hard to come by.

Positive representations of PWDs (People with disabilities) are hard to come by.

People are REALLY excited about this project, myself included. Have you been surprised by the response?

People are REALLY excited about this project, myself included. Have you been surprised by the response?